A hundred years ago, when I was in university, critical theory was beginning to influence the English curriculum. A professor introduced us to Roland Barthes’ essay on the death of the author with the memorable addition that we were welcome to attempt to argue that Milton’s Paradise Lost was about scrambled eggs, if we chose. A few years later, I was in a class with one student who found the abandonment of authorial intention offensive. I think she was disturbed by the fact that there was no “right answer.” I, on the other hand, found it oddly freeing. Samuel Johnson said

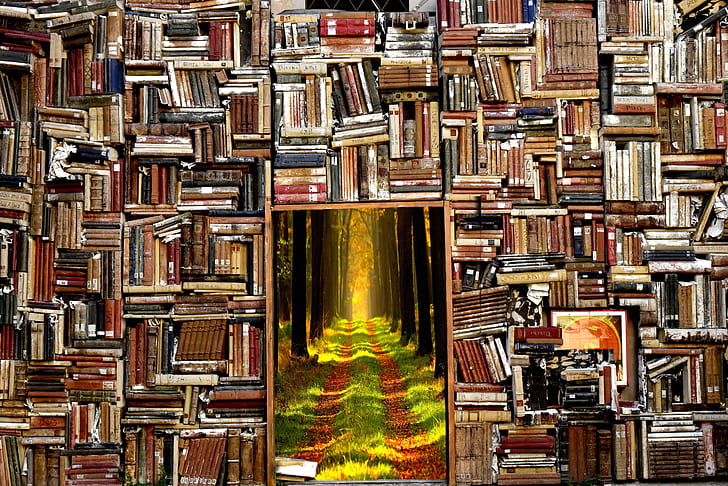

A writer only begins a book. A reader finishes it.

The way a story takes shape in the imagination of the reader is wholly opaque, perhaps especially to the author.

I picked up A Fine and Private Place by Peter S. Beagle the other day. It’s a new edition with an introduction by Neil Gaiman. He reflects on how he first came across the author and the book and how it shaped his own writing, but he also says he worried about rereading it after a long time,

What if it was not as good as I remembered? Any book you fall in love with is a collaboration between the reader and the text, and sometimes the reader who comes back to the text needs something very different from the words waiting for them: Occasionally you realise with sorrow that the book you remember did not exist, and that you made it from words that said something very different.

Neil Gaiman has said many things about books, about reading and writing, with which I wholeheartedly agree. However, Neil Gaiman is, apparently, a terrible person. I don’t know him, I didn’t know him before the most recent revelations. Does it change the fact that Neverwhere is one of my favourite books? Does it change the fact that I wish I had written American Gods? Not really.

I suppose there have always been celebrity authors – that is, authors who are celebrities, not celebrities who are authors. Hemmingway comes to mind. I remember regretting never having written to various favourite writers after their passing – Carol Shields, Ursula LeGuin, Terry Pratchett. But frankly, I always hesitate because I feel that that would be treating them as friends. And I haven’t done any kind of groundwork to call someone a friend when I can’t even ask them out for coffee, listen to their woes or their joys, hear their opinions.

After the downfall of a celebrity (and so many of them seem to fall), people can be so very outraged, seem to feel personally betrayed. I don’t understand this. For most of us these people are not friends. They are not even remotely connected to us. There are some, admittedly, who hold themselves up as role models and perhaps, if you are inclined to follow them, you have reason to feel let down. But I do think that it is possible, even desirable, to divorce their expressed ideas from their actions. When it has been suggested that Gaiman’s works should be deprecated, I find myself acutely uncomfortable. To me, cancel culture smacks of censorship. I think about artists of the past that have embraced horrifying ideals, but whose work, whose art, has the power to elevate the minds and hearts of all who are open to the power of that art. Think of Wagner, blowhard anti-semite, whose operas are not only immortal, but have influenced the art of so many other important composers and artists. Think of the facism of Ezra Pound, the boasted immorality of every second writer in history, the racism and misogyny of so many others. And yet, their work is profoundly important to me, and to anyone who thinks, because art shapes and defines minds – not directly, and not, no matter what the book-banners think, insidiously, but blatantly, sometimes gloriously, sometimes painfully…

Except that it doesn’t. Minds are shaped and defined by the work they do – by the interpretation of art and of not-art.

There is an argument to be made for keeping certain books off the shelves of school libraries, off the shelves intended for children in public libraries. These are places where children can choose what they want to read for themselves. The argument for keeping certain books off those shelves is based in reality – that not all children are able to discuss what they read with someone they trust, and who trusts them. When a child reads about the holocaust, they need to talk to someone who can lovingly and carefully explain just how horrible people can be to one another, and how learning about something may be the way not to repeat it. But taking the book off the shelves is an admission that society is failing our children. And that is a post for another time.

What can a person do? When corporations do awful things, we can refuse to buy their wares, refuse to invest, even, in some cases, take legal action against them. But the work these artists do cease to become theirs the moment they publish. The work becomes part of the reader, if it’s any good. If it isn’t, well, it will likely die. Of course, if some idiot then bans the work, people will try to find out why it was banned and more people will read it than would have if they’d just let it die. Zombie texts walk among us.

Here is what I can do. I can read and learn and read some more. And I can encourage others to face art of all kinds with an open and discerning mind. We all need to learn to think and embrace the glorious possibility of a changed mind, a shot at redemption. George Eliot said,

The only effect I ardently long to produce by my writings, is that those who read them should be better able to imagine and to feel the pains and the joys of those who differ from them in everything but the broad fact of being struggling, erring human creatures.

Or, to quote Mr. Gaiman again,

Fiction gives us empathy: it puts us inside the minds of other people, gives us the gifts of seeing the world through their eyes. Fiction is a lie that tells us true things, over and over.

So, while this author is dead to me, the art we have created together will live within me – will, I hope, shine as a good deed in a weary world. I will always be grateful to anyone with the courage to put words on paper, paint on canvas, music in my ears, or create any kind of thing that moves me, but especially that which moves me to think.