All of the books on this list share a leaning toward magic realism. In some the realism is to the fore, and in others, it’s the magic, but in every case, the author makes effective use of either or both to illuminate their story in beautiful and devastating ways.

What I love about Stardust is that it is a fairy tale with bells on, that never claims to be for children. The story is, on the one hand, a straightforward fairy story of the hero’s journey kind. On the other, it is an exploration of what fairy tales can tell us about our own stories and about our very human being.

So, if you liked Stardust for those reasons, or you see another title on this list that you loved, read on, Dear Reader. Let me know if you think of any I should add to this list. NB: the books get darker and more serious as you go down the list.

Stardust: Gaiman, Neil. Stardust. Headline, 2013.

I love all of Neil Gaiman’s writing, but this story has a vein of magic realism that is quite appealing. By placing the magical firmly in the real world and accepting the reality of magic, an author highlights the wonder that may be found in the everyday magic of reality.

The story follows Tristan, a young man of suitably unclear origins who lives in the mundane village of Wall, so called for the wall nearby, which the villagers guard, and which separates the world of Faerie from the real world. Having made a rash promise to the lovely young Victoria to fetch her a fallen star, he uses this as his excuse to cross into Faerie and pursue Adventure.

Distracted by fairy tale tropes, fable lessons, and charming and revolting characters, we follow Tristan as he follows his heart to a highly satisfying, yet not entirely predictable, happily ever after.

The Princess Bride: Goldman, William. The Princess Bride : S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love & High Adventure. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1973.

This is the book upon which the beloved film was made. And, while I adore the film as much as the book, there is much more to love about the book, including pseudo-biographical details about the author and his motivation to write the book that don’t come into the film at all. In the book, the young boy to whom the book is read, is William Goldman himself, and The Princess Bride is read to him by his father – who, as it turns out, abridges the book to a profound degree. As an adult, Goldman decides that he needs to write the “good parts” version of the book, the version he remembers and loves from his childhood.

A fairy tale adventure that is wickedly funny and funnily wicked and that calls to the heart with bittersweet memories of childhood visions of what our future could be.

Nettle & Bone: Kingfisher, T. Nettle & Bone. Tor Books, 2022. Hugo Award winner 2023

Nettle & Bone is another fairy tale for grown-ups, if not adults. While lots of fairy tale elements are present – three sisters, prince, witches, three impossible tasks, quest, and so on – the novel touches on some, not darker (some of the original fairy tales were quite horrific), but more modern themes such as domestic violence and self-empowerment.

What attracts me to this book is the fairy tale matter-of-factness, combined with clever wit and the nearly all-female cast. This quotation caught my eye, and my fancy:

“How did you get a demon in your chicken?”

“The usual way. Couldn’t put it in the rooster. That’s how you get basilisks.”

I love that the character obviously believes everyone knows what the usual way is. And, honestly, is there a more unlikely object of demonic possession than a chicken?

Neverwhere: Gaiman, Neil. Neverwhere. Headline, 2000.

Neverwhere is less obviously a fairy tale than Stardust, also by Gaiman, but it, too, contains fantastical creatures (and people) and a hero’s journey. The characters are out of fairy tales, folk tales, horror stories and more, and there are philosophical questions that begin with those familiar in fable, but progess to the profound and timeless questions of what makes us human.

Neverwhere is Neil Gaiman’s first solo novel and it is a shining example of what a good writer can do with a fairly simple idea. Homeless people and panhandlers are often treated as invisible. What if that’s a survival trait? And what if it’s catching?

Richard Mayhew is a middle-everything – class, looks, education – in a job that he rather wishes were dead-end, except that his domineering fiancée won’t have it. One day, on his way to a dinner that he has every reason to expect will be a disaster, they come across a young woman who looks to be homeless and is most certainly injured. Richard insists on helping her, to the dismay of his fiancée, but what he doesn’t realise is that, simply by noticing Door and the world she inhabits, he has erased himself from his world. His fiancée, his closest friend, his colleagues, no longer recognise him. When his landlord attempts to rent out his apartment while he’s in it, he decides he’ll have to take action. He seeks out the nearest person who looks homeless to him and asks to be taken to the next night market, and embarks on a journey as epic, harrowing, and soul-defining as anything out of the classics.

Gaiman mingles high adventure, fantasy, and gothic horror with a matter-of-fact style that is quite compelling. The language pulls the reader in, makes you crave more, even when you’re not sure you really do want more.

There is some fairly graphic violence, which, if you’ve read the Sandman books won’t come as a shock, but it’s worth reading the rest of the book even if you have to skip over a page here and there!

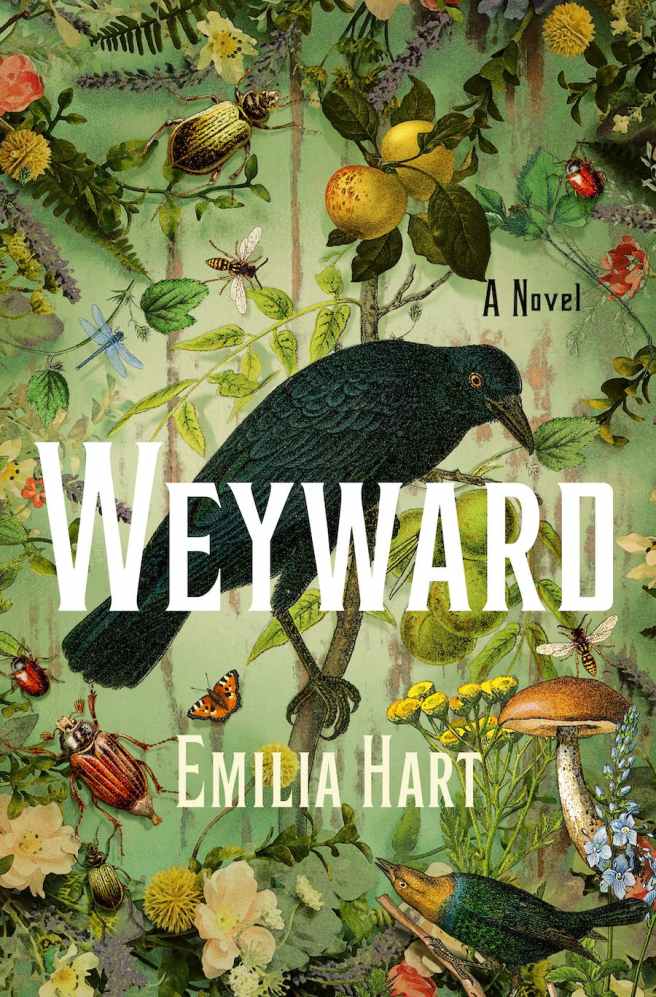

Weyward: Hart, Emilia. Weyward. St. Martin’s Press, 2023.

Weyward is a bit of a departure for this list as it isn’t funny and there isn’t much of the fairy in this tale. There are witches of a sort, and there is a kind of quest. Told through three timelines is the story of the Weyward women. Beginning with Altha, in the 17th century, on trial for witchcraft, through the discoveries of Violet, unknowing 20th century daughter of a 19th century Weyward woman, to Kate in the 21st century, fleeing an abusive marriage and the haunting memory of the death of her father, Violet’s brother, we see how the threads of magic may weave a beautiful tapestry. That tapestry, however, may be beautiful and useful, or it may be beautiful and tragic.

This story is predominently about the survival of women through their connection with Nature and with each other. As Kate regains these connections, gathers up the broken threads of her Weyward tapestry, the story of how women will rise again and again, and rise triumphant over the foulest of abuse.

While the book has and evokes anger and sorrow, and might descend to the depressing, the beauty of the writing lifts the reader above the subject matter, to make the story visible in all its glory and all the more effective.

Ninth House: Bardugo, Leigh. Ninth House. Flatiron Books, 2021.

Ninth House is the first in what is expected to be a trilogy following the, well, adventures might be too weak a word, of Alex Stern, a young woman with an appallingly troubled past who is gifted/cursed with the ability to see ghosts.

This book is dark and violent, horrific and funny, in that I-really-shouldn’t-be-finding-this-funny way that characterises many well-written, very dark fantasy stories. And it is well-written.

Leigh Bardugo is a hugely popular writer of Young Adult fantasy, but this book most assuredly does NOT belong on the Young Adult shelves. Set in current day Yale University the book has a thin veil of story that is occupied with a fairly familiar fish-out-of-water theme, but it viciously tears that veil aside to confront some difficult ideas. Rape, murder, excess, and some lesser, but no-less impactful horrors follow one from another, and it can be a bit overwhelming.

But Bardugo makes it worth the reader’s while. The setting is compelling, growing from that familiar/not-familiar tension that underpins magic realism. The main character is snarky, desperate, grieving, wounded, and heroic and so well drawn that I expect there isn’t anyone who doesn’t either identify with or wish to protect her. Ninth House won’t appeal to some – it’s too dark, and too oppressive. But the prize is there for those who can find the wherewithal to finish.

Babel: Kuang, R. F. Babel. HarperCollins, 2022.

Babel is a serious book about serious matters. Kuang tackles racism, poverty, slavery, eugenics, and all manner of social horrors in a truly gripping story. The characters are beautifully drawn, as are all the settings. The prose is thoughtful but never distracts from, nor is over-shadowed by the terrible machinery of the plot.

Brought to London in 1828, Robin Swift is the child of a Chinese woman by an unidentified father. He is raised by his so-called benefactor, encouraged to maintain his mother tongue and yet to repudiate his Chinese heritage. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that Robin’s fate is to provide translation magic for the sustenance and growth of the British Empire.

Robin is torn between the ideal life of a scholar that he imagined and the realities of serving as a tool for crushing opposition to the Empire. Kuang’s ability to articulate the pain of this dichotomy invites the reader’s investment in the character and in the story itself.

The setting of the novel is recognisable as Oxford and England at the height of the British Empire. Like Philip Pullman in His Dark Materials, Kuang imagines for us a few twists that shift the balance of power to Oxford, and provide a focus for the rebellion against that power.

The novel is dark, and the end is ambivalent, but because of that, the story lives in the imagination long after the book is finished. The questions that are raised have no easy answers but as long as the question exisits, answers must be sought. Kuang invites us to continue seeking.